Ready-to-implement tips for function-based behavior intervention planning

Dealing with behavior challenges can be draining. As you begin to empty your toolkit of strategies, that frustration only grows. Many times this leads to referring the student to your campus child-study or MTSS team so you can get additional strategies to support the student. Sometimes these meetings are quick and simple. Other times, it can feel like you’re not getting anywhere. If you’ve ever sat in an RTI meeting struggling to figure out the next steps when it comes to planning behavior interventions, this post is what you’ve been looking for.

Planning behavior interventions with your intervention team

The first step to planning effective behavior interventions is to consider the function of the behavior. Read more about how to collect data to determine the function of a behavior.

After you’ve had a chance to discuss concerns and brainstorm possible functions of behavior, it’s time to create your behavior intervention plan.

This is ideally done with all the teachers who work with the student. This makes sure everyone can agree on the next steps and commit to implementing the behavior interventions with fidelity. Consistency is critical when it comes to intervention. Therefore, you’ll want to make sure everyone is on the same page and feels prepared to put the plan into action.

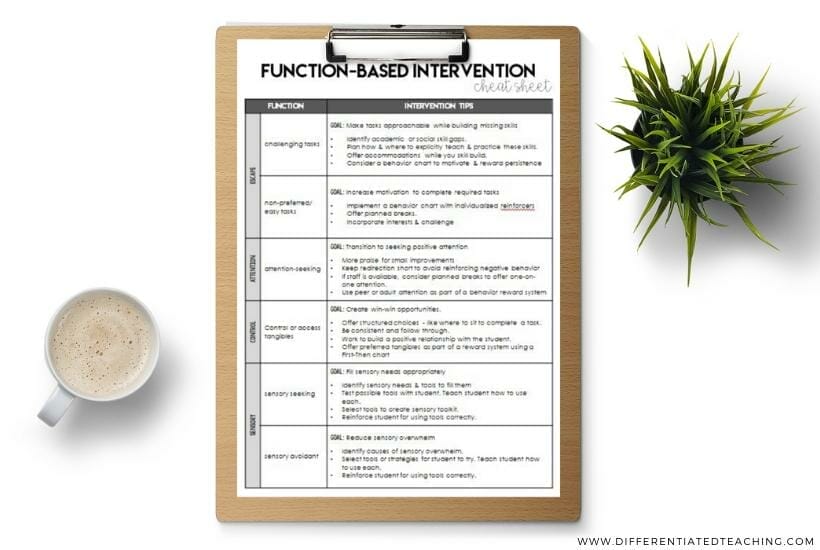

As you begin to select interventions, consider the function you identified. Below I’ve outlined strategies for each of the major functions of behavior. You can also grab the cheat sheet version by entering your email below.

Function: Escape from Tasks or Situations

Escape behaviors fall into two categories. Students are either trying to escape something that is too hard to something that they deem boring or too easy. Once you’ve determined that a student’s motivation is to escape, you can usually determine which category they fall into.

Students who are trying to escape challenging tasks are often overwhelmed by the work they’ve been given, and it is easier for them to be the kid causing a disruption than to be the kid who doesn’t get it.

Kids who find tasks boring or too easy often misbehave as a way to fill the time and spice things up. This is why your approach to both situations needs to be slightly different.

Escape Challenging Tasks

If your team identifies that a student’s behavior is the result of academic difficulties or social skill gaps, determine how you’ll fill those gaps. This means creating a plan for how you’ll explicitly teach those skills and offer opportunities for practice.

If academic gaps are present, you’ll also want to create a plan for how teachers can make accommodations and adjust the work the student is given to accurately assess what s/he knows.

For example, if a child’s data indicates that he may be struggling with computation skills or fluency, how can his teachers make sure he is able to access and show mastery of the curriculum while he builds these skills?

The idea is that if a student’s behavior is an attempt to avoid a task that is too challenging, we have to take a two-pronged approach to behavior intervention. We need to provide explicit instruction and practice to fill the skill gap AND we need to prevent additional skill gaps by adjusting the learning environment while the child builds those skills.

Depending on the student, you can also use a behavior chart to help boost motivation and persistence. Offering multiple opportunities to earn rewards throughout the day can be a great way to encourage a student to put in their best effort despite challenges.

Escape non-preferred, “boring”, or easy tasks

If your team determines that the student’s behavior is an attempt to avoid non-preferred or boring tasks, create a plan for how to make these tasks more enticing for her. Some students lack the internal motivation to want to do their best when their work isn’t engaging. Adding external motivators can be a huge help.

This might include creating a behavior reward system, where she can earn preferred activities or tangible rewards for being compliant and acting appropriately towards teachers and peers.

It could also mean offering opportunities to work in areas of interest. For example, if a student is interested in video or YouTube, the student may be offered the choice of creating a video to share their research or writing a report.

Similarly, teachers could offer a choice of enrichment or challenge tasks when students complete their work. This serves to engage the learner and offers the motivation system needed to push them to complete less desirable tasks.

Both of these are options that are highly successful for students who are not completing tasks due to a lack of motivation or interest.

Function: Attention-Seeking

If your team identifies the challenging behavior as an attempt to gain attention from peers or adults, you’ll want to flip the script by creating a plan that offers positive attention to reinforce desired, school-appropriate behaviors.

For many students who demonstrate these types of behaviors, the need is for attention regardless of whether it is positive or negative.

You need to purposefully provide consistent, enthusiastic praise when the student makes small steps toward positive behavior in class. This needs to be done with an equal or higher level of energy as any redirection is done.

Linger and offer a few sentences when praising, but when redirecting keep your statements short and to the point. Refrain from lingering on negative behavior, but continue to redirect when appropriate.

The goal is to help the student internalize that he receives more attention for positive behaviors than negative behavior. This will result in a shift toward more appropriate behavior if done consistently over time.

If you’ve got the support of your administration or other staff, you can also build breaks into your student’s schedules. These breaks should be a chance to get the one-on-one attention the student craves. Have adults stop in and chat with him, take him on short walks, etc. as a chance to get the attention he seeks.

You can also incorporate opportunities for attention into your reward system. Many students who demonstrate attention-seeking behaviors would be happy to work for some undivided adult attention. For example, you might offer lunch in the classroom or a chance to play a game together.

Function: Control or access to tangibles

For students who are attempting to gain control or access to tangible, your goal is to create a win-win situation. Structured choices can be a great opportunity to allow freedom of choice while still maintaining control of your classroom.

For example, you might offer a student the opportunity to work at their seat or on the floor. You could also offer the choice of using a pencil or pen. The idea is that you’re addressing the function of the child’s behavior without the stress of the negative behaviors.

One thing to consider with this strategy is to be sure to have a clear time limit for the child to choose and let them know from the get-go what your choice will be if they haven’t decided. This allows him structured freedom and can reduce power struggles.

Once you’ve given the choices, walk away for 30-seconds to a minute. When the time is up, return to see what the student has selected.

A first-then chart is another great strategy for offering control. The visual provides a clear understanding of what the student must complete before they access their desired activity or tangible reward.

Finally, you’ll want to consider how you redirect and communicate with these students. Some students will escalate when confronted in the proximity of peers. This is often an attempt to save face and maintain their image. Taking time to speak privately with the child can reduce this issue and get more compliance.

Function: Gain or reduce sensory input.

Sensory-seeking or avoidant behaviors are not related to interactions or interpersonal interactions. Instead, they are caused by the body’s internal need for sensory regulation.

If your team identifies behavior as sensory-seeking or avoidant, you’ll need to craft an intervention plan that offers the sensory input the child needs in a school-appropriate format.

For example, a student who frequently chews on things or hums may be seeking oral input. Offering a chewy necklace or similar alternative may allow the student to fill this need without causing disruption to peers.

This may include using sensory tools – like chewy necklaces or noise-canceling headphones. When you introduce these fidget tools, you’ll need to explicitly teach the student the rules and expectations for how they’ll be used and stored.

Grab the Behavior Intervention Cheat Sheet

Take these ideas to your next meeting with this click-and-print cheat sheet. Just enter your info below to access it now.

Next steps for Planning the Behvaior Intervention

Once you’ve created a function-based intervention plan, you’ll want to get together as a team and review the data every six weeks. As the classroom teacher, you’ll likely be responsible for bringing most of the data to this meeting.

Be sure to record when the next meeting will be held and who you can contact if you have questions or concerns about the planned behavior intervention before you leave.

If you enjoyed this article and want to learn more about behavior intervention, check out these additional resources: